It’s been a few months since my last post but I’m happy to say that I’m finally on the other side of several projects that have taken up considerable time and attention (in addition to daycare and quarantining with my family in the mountains of western North Carolina). In particular, since July 2020 I’ve been working hard on a report that will get its public release Tuesday, February 9 by the Council on Strategic Risks where I am a Senior Fellow. (Update: I left the organization in August 2022).

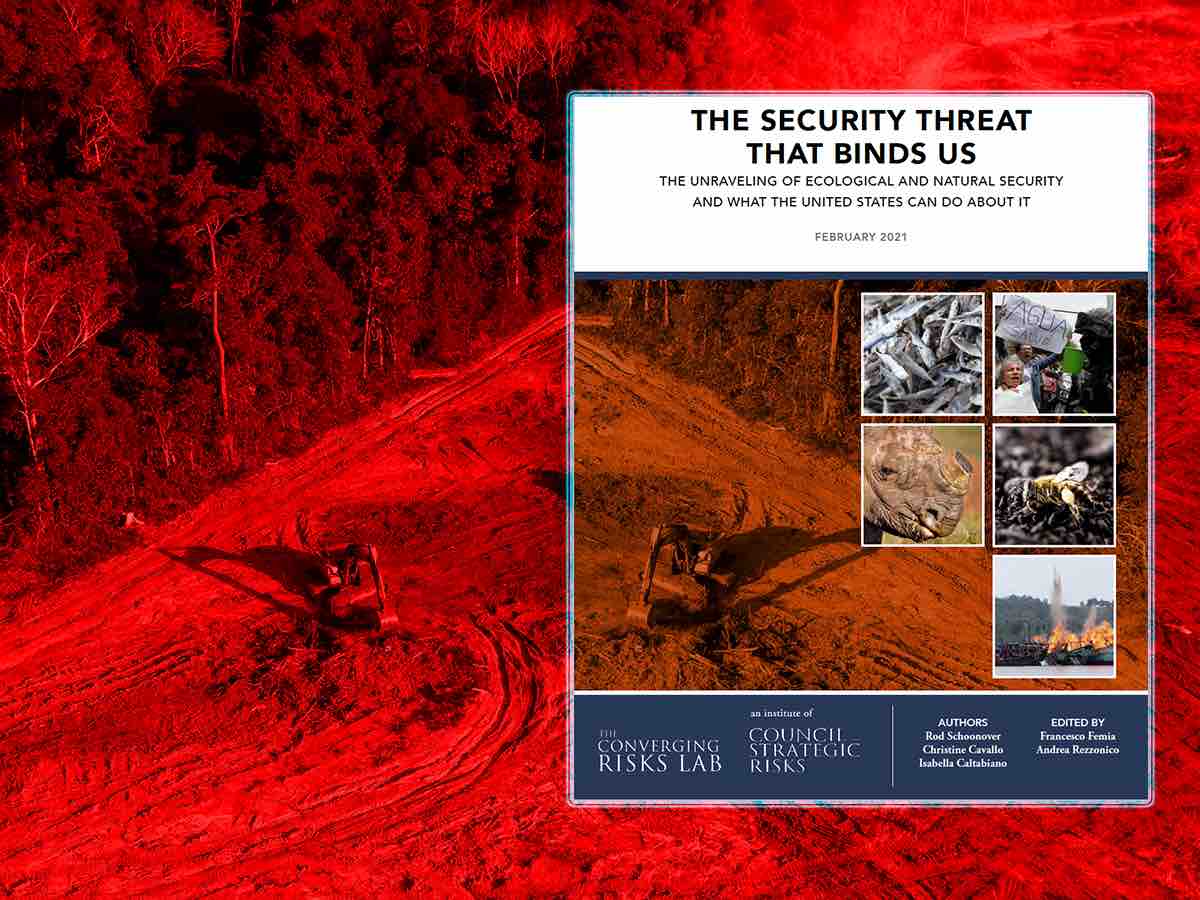

The report, titled by the editors The Security Threat that Binds Us: The Unraveling of Ecological and Natural Security and What the United States Can Do About It, describes the pattern of ongoing global ecological disruption which is both part of and separate from climate change. In addition to stresses to water, food, wildlife, forests, and fisheries, my coauthors Christine Cavallo, Isabella Caltabiano, and I look at patterns of ecological change and losses of ecological function from a societal and security perspective.

The document analyzes the implications of these changes for human, national, and global security, looks at the future of ecological security (spoiler alert: it’s not rosy), and offers eight pillars of recommendations for U.S. policymakers to help address the problem. I believe that many of the concepts in the document have never been articulated in a security context before.

The basic concepts underlying this report started to gel in my head around 2012 while working in the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research. As one of the very few scientist-analysts in the intelligence community, a primary daily responsibility was to stay on top of the rapidly evolving scientific literature relevant to my portfolio (environment, science and technology, and health) while also ingesting large amounts of classified reporting. At the same time, I interacted with talented civil and foreign service officers at State that handled some of the most important accounts relevant for a changing planet. Many of the officers served with distinction, if out of the limelight, in the Bureau of Oceans and International Environmental and Scientific Affairs, known also as OES.

During this time I came to understand more deeply that stresses on fisheries, forests, wildlife, and biodiversity were seriously underestimated from a societal and security perspective. While I had success discussing with senior policymakers many aspects of climate change, water stress, and food insecurity from this lens, addressing ecological disruption similarly was then a step too far.

From 2012 to about 2016, the intelligence community was able to produce important work on wildlife trafficking and illegal fishing, however. But the national security community is not well suited to address problems that don’t have identifiable malign actors. (This is part of the reason why I, and others, have called for the national security architecture to be rebooted to meet the actual risks coming our direction.)

One of the most terrifying reports I ever read while in government was not about terrorism or weapons of mass destruction but rather the 2019 global assessment report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). It was immediately clear to me that themes outlined in the sprawling document had implications for rather serious security outcomes, such as political stability, social cohesion, human security, and the like.

But the IPBES report made zero waves in the security community. That needs to change, and hopefully reports like The Security Threat that Binds Us can provide a framework going forward.